Replayable Puzzles

What Makes a Puzzle “Replayable”—and Should It Be?

Activity books often mix in specialty puzzles alongside standard formats. I often notice only one or two of these oddballs in a given book, but those are what I consider "replayable" in spirit. Not because the same puzzle is played twice, but because the format itself invites further exploration.

A book full of Sudoku puzzles is technically repeatable, sure—but a Sudoku app? That starts to feel like replayability in its purest form.

When I sit down to construct puzzles, I don’t treat replayability like a yes-or-no question. It’s a dial I adjust. For example: a sub-anagram puzzle might only be fun once or twice before it turns into a grind. But something more logical or visual might get three to six variations—enough to give the solver a taste and a path from easy to challenging. Even Hashiwokakero, which is a standard format, might be new to some readers. In my experience, two puzzles don’t quite satisfy. Six tends to strike the right balance.

The Replayability Litmus Test

So what really makes a puzzle replayable? Here are my three criteria:

- A non-trivial mechanic

- Random starting conditions

- A single solution for each setup

That third one? It’s usually treated like gospel in logic puzzles. But I don’t always subscribe. Humans have decreed there must be a single correct answer, but I sometimes design puzzles that allow multiple solutions. If the puzzle clearly tells the solver the goal is "highest score" or "most efficient path," then ambiguity becomes part of the fun. It’s the DMZ between puzzles and games.

Take The Marvelous Mulberry Portal, for instance—a visual puzzle where players win by summoning either three monkeys or three weasels. Two paths, both valid. The replayability comes not from solving it again, but from discovering there’s more than one way to win. I hope that opens the door for players to question assumptions, explore variations, or even revisit what they may have missed.

Where Replayability Fails

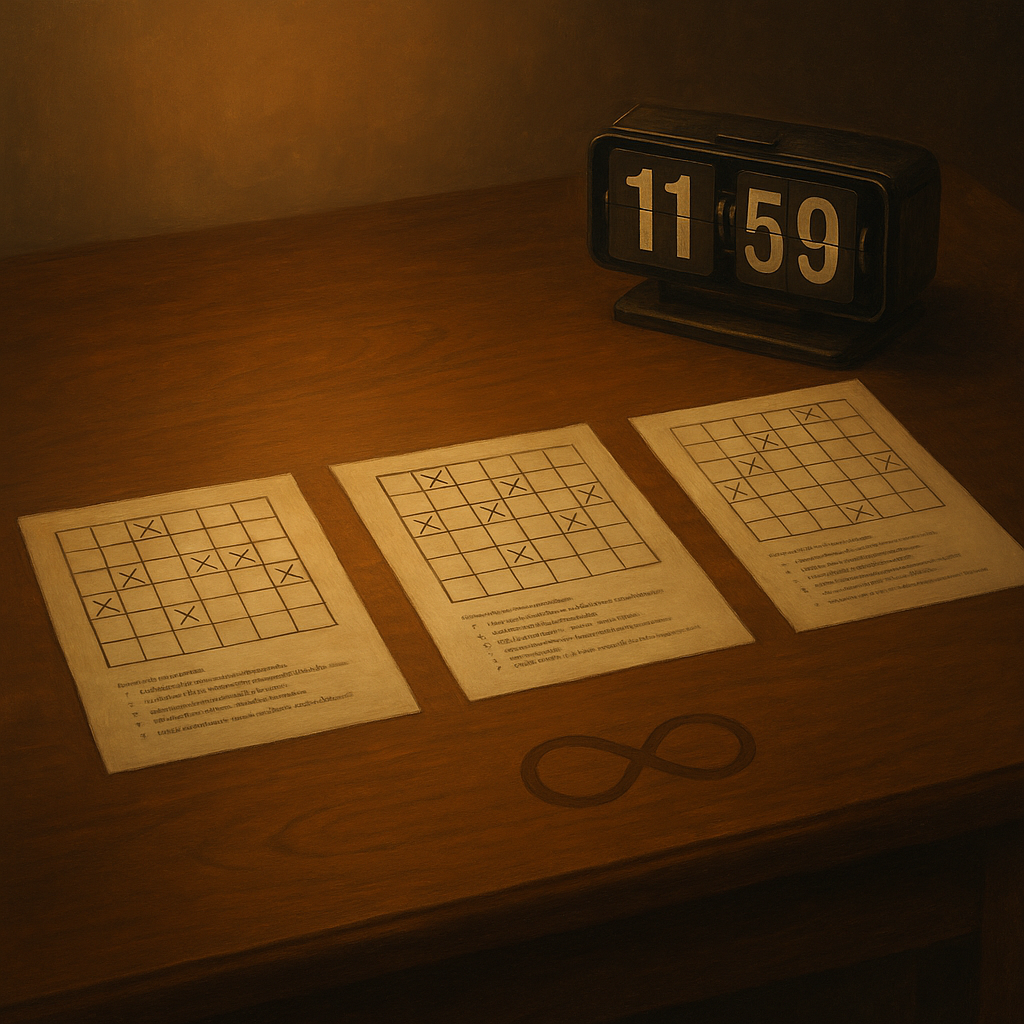

I’ve had my own flops. One concept called Myrdle was meant to parody Wordle clones—a massive 100x100 grid where you fill in as many 5-letter words as possible. It looked great on paper. But once I started building, I realized the core mechanic was mind-numbingly boring. The repetition killed it.

Take Tic-Tac-Toe—it's the textbook case of a puzzle that falls apart after a few plays. The mechanic is so basic and predictable that once you understand the strategy, there's nothing left to explore.

Even a more complex example like Nim follows this pattern. At first, it seems like a battle of wits, but once you discover the underlying binary strategy—known as the Nimber or XOR principle—it becomes a deterministic game. The mystery vanishes, and with it, the desire to replay.

That kind of predictability is exactly what replayable puzzles must avoid.

And sometimes, the death of replayability is more subtle. I once used cute icons in a puzzle app. My wife said it made the whole thing look childish. I was afraid the aesthetic might turn away solvers before they even gave the puzzle a shot.

But When It Works...

Some puzzles do have legs. One of my best-received puzzles was a four-part locked-room mystery series called Sprocket Thistle Manor. Reader feedback suggested people were engaged across issues—and genuinely invested. My visual puzzle formats continue to surprise me with how strongly solvers respond to them. The ones that blend logic, hidden patterns, and storytelling seem to stand up to repeated plays.

Sudoku offers a great metaphor: every puzzle looks random, but the solver knows there’s a rigid structure underneath. That promise of order is the real invitation to play again.

Even the Puzzle Baron logic books, with their 200 nearly identical 4x5 layouts, are a testament to how far theme and surface variation can carry a format. It may not be true randomness, but the illusion works.

Should Puzzles Be Replayable?

If I had to choose, I’d rather be remembered for a brilliant repeatable format than for a single elegant puzzle. Einstein might have designed the most difficult logic puzzle ever, but Ernő Rubik has a cube named after him.

Replayability isn’t just about longevity. It’s about building something people want to return to. And sometimes, that’s the best puzzle of all.

Visit The Hidden Frame

If you’re curious where puzzles like The Marvelous Mulberry Portal live, I keep them tucked away on a page called The Hidden Frame. It’s a quiet little corner of the web where you can play, explore, and maybe come back again tomorrow.